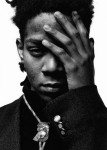

ALAA EL ASWANY - DE VOLKSKRANT 12 01 2007

Voici mon premier portrait pour le quotidien hollandais "de Volkskrant". Il s'agit de l'écrivain égyptien Alaa El Aswany dont le premier roman "L'immeuble Yacoubian", publié aux éditions Actes Sud, vient d'être traduit en hollandais.

Je l'ai photographié à l'occasion de sa venue au festival de littérature de La Haye le 09 01 2007.